Brave (and rather confusing) new world

I want to do what I set out to do when I went to Manchester. I want to be an actor. In fact, now, actors don’t even have to be members of Equity any more – oh, the irony. But now I’m too old to play Hamlet at the RSC, or be the new Malcolm McDowell – and the baggage of having been a comedian keeps getting in the way.

Casting agents see me as a comedian. Writers see me as a comedian. Producers see me as a comedian. People in the street see me as a comedian.

In the world of straight drama, the distrust of people who have identified as comedians is very strong. They fear some kind of latent anarchy – that I won’t take it seriously enough. But as grotesque as many of my creations have been, they were all fundamentally acting jobs. They were all as carefully constructed – Baron von Richthofen, Eddie Hitler, Dick from The Famous Five – the programmes they were in just had a different goal in mind.

I set about being a non-comedian.

Except that it’s hard not to fall back into it sometimes. How could I resist the pull of The Bonzos? Or the joy of The Idiot Bastards? Although in my defence I’d say The Bonzos were beyond comedy, they were more like art. And The Idiots at their best were so relaxed that the pressure to perform, to be some kind of berserker, was practically non-existent.

There are some false dawns.

I audition for a director called Nick Murphy who casts me in a programme he’s making called ‘Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster’. This is in 2006, and it shouldn’t be confused with the 2019 series Chernobyl – though anyone watching them both couldn’t fail to recognize the spookily similar approaches to the story.

Nick is a delightful human being who takes his work very seriously but is not unaware of the pomposity of people who take things very seriously – he keeps pricking his own bubble. He’s come from the world of documentaries, is moving into drama, and our programme is a halfway house, a docudrama.

I’m trying to move from comedy into drama. We get each other.

The camerawork is purposefully scruffy, as if struggling to keep up with real events. There’s a script, but he wants us to treat it as a guide and roughen up the edges to add to the authenticity – no one in the real world talks in proper sentences. We’re shooting in Lithuania in Soviet-era locations. Everything is about realism. The finished programme is cut with real footage from the time and it’s hard to see the joins.

I’m in my element: I understand cameras, I know where I am in the shot, I know what he’s going for, I’ve researched my character – an actual historical person called Valery Legasov – it feels like it’s real, and I’m good at improvising. Look at me, Sandford Meisner! Look at what I’m doing. It’s one of the best things I ever do.

Unfortunately it goes out as part of a series called Surviving Disaster and the other episodes, made by other people, about other disasters, are . . . a disaster. No, that’s harsh, but they’re a different style – strange confections of sugary melodrama and tabloid journalism. So ‘Chernobyl’ gets lost. You win some, you lose some.

I lose myself in a couple of presenting jobs. I make thirty-six episodes of The Dales – which is me wandering round the Yorkshire Dales looking at things and talking to people. I make fifty episodes of a daytime series called Ade in Britain – a pun on ‘Made in Britain’ – in which I wander round Britain looking at things and talking to people. I make a primetime series called Ade at Sea in which I wander round the coast of Britain looking at things and talking to people and prove that I’m all at sea.

As I’ve said before, it would be nice if my life fell into neat compartments, but it just won’t. Life after comedy is frankly a complete bloody mess: ‘Chernobyl’; the presenting jobs; The Bonzos, The Bad Shepherds, and The Idiot Bastards; forays into reality TV; Hell’s Kitchen (who would have thought the final would be between Crystal Carrington from Dynasty and Vyvyan from The Young Ones); Celebrity MasterChef (winner 2013 – take that, Janet Street-Porter and Les Dennis); Comic Relief does Fame Academy.

I’m a man without a focus.

But one thing all this floundering around does is confuse people – and this is probably the best thing I can do – because now they don’t know what I am at all, which is marginally better than just being an ex-comedian. There’s quite a lot of ‘me’ in that furious list above, and ‘me’ is very different to Vyvyan or Eddie Hitler; ‘me’ has started to look less like a berserker, and more like . . . a human being?

I slowly become what some people call a ‘jobbing actor’: forty-six episodes of Holby City, playing a doctor who wears his heart on his sleeve (which as any doctor knows is the wrong place for it to be); Miss Austen Regrets, a period drama in which I play Jane Austen’s brother, while Greta Scacchi plays my other sister Cassandra; War and Peace, in which Greta is now my wife – is this incest?

Even Star Wars – though I discover this has roots in my comedic past.

My first thought when my agent calls to say they’re offering me the part is, Imagine what Fred and Bert would think! Fred and Bert are my grandsons and they’ve got the Top Trumps version of Star Wars – imagine if I suddenly turned up in the next pack of cards. (I do actually become a collectible trading card.)

It turns out I’ve been hired for a similar reason. The director, Rian Johnson, was a fan of Bottom in his student days. He tells me he first became aware of Bottom as a book of scripts, rather than as a TV programme, and shot one of the episodes as a film while at film school. He’s basically done what I did with The Goon Show scripts, only with better equipment and actual actors. But we’re both getting something else out of this experience.

Filming schedules in the modern era generally don’t allow the time to go down the full Meisner route. A friend who worked with Keanu Reeves in the nineties says he places a towel over his head in between set-ups to keep the outside world at bay, which obviously works for Keanu, but sounds a bit unsociable. I develop a method that works for me: I just learn my lines to death.

You may have seen me in Hyde Park doing my four-mile stomp around the perimeter with pages of script in hand, chuntering at the trees. Luckily the park is so full of nutters I don’t look too eccentric.

I repeat them over and over again. By the time I say them in front of camera I’ll have said them a minimum of 500 times. The lines go on a weird journey of their own: they start off being an exercise in memorizing; then, as a kind of muscle memory begins to work in my mouth, they become almost meaningless; then the meaning slowly drifts back, but by this point the thoughts and the words are no longer two separate processes and it hopefully sounds like I’m actually thinking them.

On the set of A Spy Among Friends, Damian Lewis remarks that I turn up ‘camera-ready’, but that’s not quite the aim: I want to be so completely prepared that I can spend my time off-camera having a laugh and swapping stories – which is what the filming day is mostly about in my view. Keanu doesn’t know what he’s missing.

Though my line-learning method fails when I do Star Wars. It’s hard to learn your lines to death when they won’t tell you what they are.

My friendship with Rian doesn’t open the security level that would permit me to read the whole script. The production is obsessed with secrecy. I’m allowed a brief read of some of my lines, in a locked room with a production assistant looking on, a week before filming, but I’m not allowed to take a script home. And when I show up to film each day I’m given the relevant scene with all the other characters’ lines redacted.

You can’t see what the other characters are saying?

That’s right.

But that’s insane.

I always knew my readers would be wise.

It’s only at rehearsal on set that I find out what the others are saying. It’s hilarious. Imagine my surprise when I turn up at the premiere and find I have the first line in the film. This might be why most of the minor characters in Star Wars seem so ‘spaced out’ – they really don’t know what’s happening.

Over recent years I’ve been involved in several programmes that are labelled comedies: Sara Pascoe’s Out of Her Mind; Daisy Haggard’s Back to Life; and Cash Carraway’s Rain Dogs. I’ve seen them variously described as a sitcom, a dark comedy-drama, and a black comedy. I had to think very hard about doing them (even though I went through two rounds of auditions for Rain Dogs – two rounds of a scene in which I had to simulate masturbation – life can seem pretty unedifying at times).

Sara’s Out of Her Mind is largely autobiographical and I play a version of her actual dad, and what drew me in was the emotional content. There’s a scene where her dad is apologizing to his ex-wife, played by Juliet Stevenson (the second time we’ve played a divorced couple). They’re preparing for their daughter’s wedding and he apologizes for not having been there, and it just broke my heart.

In Daisy’s Back to Life I play a rather gruesome character, John Boback, someone who had sex with his daughter’s best friend. But Daisy writes so brilliantly about what it is to be human, about how messy and complicated it is, and she gives Boback a great escape from being a two-dimensional ‘wrong ’un’ – his genuine grief for his dead daughter. There’s a scene where he visits her grave and sings a song she liked, and he loses control and can’t get through it.

In Cash’s Rain Dogs I’m playing a scurrilous letch called Lenny. He’s a pervert and a sex pest, but in amongst the sordid world Cash creates, he emerges as a complicated man with a heart, a man who cares for Daisy May Cooper’s character – a kind of father figure.

None of these can be described as comic turns, even if they have some humour in them. The truth is that a lot of real life is bleakly amusing. Sometimes the tragedy is funny. This is what has always drawn me to Waiting for Godot.

It’s a long way from the world of the berserker though.

The older my own children become, the more I connect with playing fathers. It’s a privileged role, and perhaps because I had such a strained relationship with my own dad I find exploring fatherhood irresistible.

In War and Peace I play the jolly patriarch of the Rostov family, Count Rostov. Once I’d got through the audition and landed the part I read the book for the first time. I had to keep reading bits out to Jennifer because the descriptions of the count sounded just like her dad – the soul of the party, the generous host, the man who hated snobs. Tom Harper, the director, does a brilliant thing in the early rehearsal period, and makes us have a couple of ‘family’ meals together to increase the familial bond between us. So pretending these people are my family becomes second nature: Lily James becomes my daughter, and Jack Lowden becomes my son. And . . . the love I develop for them feels genuine. Is that mad?

It still feels genuine now, years later. I’ll see them on screen doing other things and I’ll be willing them to be brilliant just like I do with my own children. This happens with all my fictional children: Morfydd Clark from Interlude in Prague; Molly Windsor from Cheat – even though the fictional relationship is combative, I still feel paternal towards her off-camera. My actual daughter Beattie appears with Lily in The Pursuit of Love and I’m filled to bursting watching them on the screen together.

Where’s the berserker gone? This bloke’s in tears most of the time.

This is like a berserker who’s hacked his way through 1,000 Anglo-Saxons and once he’s killed the final one, he looks round at the trail of devastation, and weeps.

I finally get to the RSC. It only takes forty-two years, but I get there. Twice. First as Malvolio in Twelfth Night and more recently as Scrooge in A Christmas Carol.

In A Christmas Carol there’s a scene in which the Ghost of Christmas Past takes Scrooge back to his schooldays and shows him the lonely schoolboy all on his own when the other boys have all gone home. In my time at school I was often left there during the twice termly ‘exeat’ when all the other boys went home for the weekend.

During every performance it’s always a triggering moment for me, this reliving of a similar experience. A kind of catharsis. It’s a similar idea to blues music, which is often about misery, but isn’t miserable in itself – singing the misery through can be an uplifting experience.

It’s practising being human.

On the other hand, I find myself playing a lot of complete bastards these days, probably because I’m a white, middle-class, middle-aged man, and we’re pretty much to blame for everything that’s gone wrong in the world. These parts mark me out as the villain: I’m an absent father in One of Us and Out of Her Mind, a bullying dad in Cheat, a bullying husband in The Pact, a sexual-abuser type father in Back to Life, a member of an actual paedophile ring in Save Me, and a captain of the First Order in Star Wars, and we all know they’re complete bastards.

Though, incidentally, I have a little trick when I play Captain Peavey. His lines are fairly formulaic – he’s Admiral Hux’s second in command, a minor baddie on the bridge of the Resurgent-class Star Destroyer Finaliser – but I invent an internal monologue for him: he doesn’t agree with everything the Empire is up to. He isn’t a rebel, he doesn’t have an alternative plan, he’s no revolutionary, but before every take I make him think about oranges.

It’s a childhood memory about a planet that had oranges. He can still remember the smell of the zest, the taste of the juice, and the deep colour of the skin. That planet has, of course, been destroyed, and he’s never seen an orange since.

Of course we feel no sympathy for him, because he’s an officer in the First Order, and therefore just a self-pitying complete bastard.

Over the last five years I’ve been fatally run over by a lorry on the A1, I’ve been stabbed to death twice, I’ve been killed with a blow from a Breville sandwich toaster, I’ve shot myself in the mouth, I’ve died of cancer, and I’ve been incinerated on a spaceship.

So what are the writers trying to tell me?

It’s obviously part of the re-balancing, after centuries of white, middle-class, middle-aged men having everything their own way, and I’m all for it, but that doesn’t stop it feeling weird.

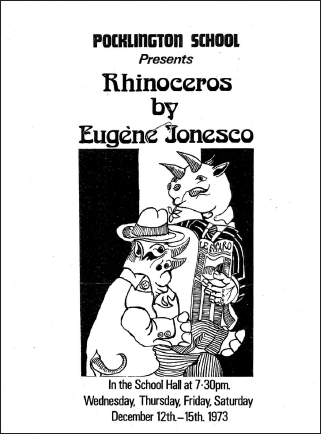

At school I once played The Logician in Ionesco’s play Rhinoceros, and he has the following exchange:

Logician: Here is an example of a syllogism. The cat has four paws. Isidore and Fricot both have four paws. Therefore Isidore and Fricot are cats.

Old Gentleman: My dog has got four paws.

Logician: Then it’s a cat.

It’s the kind of joke that drew me to the Theatre of the Absurd in the first place, and I always thought that syllogisms were essentially jokes, that they would always throw up something logically preposterous. And funny.

But the current syllogism is this: white, middle-class, middle-aged men are responsible for most of the iniquity in modern Britain; I am a white, middle-class, middle-aged man; therefore I am responsible for most of the iniquity in modern Britain. It’s not quite as funny, is it? Well, not to me.

When I’m not being slaughtered for the sins of my age, race and gender I’ve started playing authority figures. I’m a deputy chief constable in Prey, I’m another deputy chief constable in Bancroft, and more recently I’ve been promoted to head of MI5 in A Spy Among Friends. These aren’t berserker roles.

In The Trick I’m the vice-chancellor of a university – he probably knows Latin, probably knows how to conjugate and decline, and what the words pluperfect and transitive mean. This is the establishment. I have become the establishment. Some people think this is a stretch from Vyvyan, but you have to remember he was a medical student – a lot of the medical students we met at uni were similarly unstable in their youth but they all grow up to be consultants, magistrates and general pillars of the community.

The berserker is nowhere to be seen.